Africa free trade pact raises hopes of prosperity

Great article in FT about African trade.

While Charles Oppong and three other drivers prepared to spend a ninth night sleeping under their trucks at a border post, officials from Ivory Coast and Ghana blamed each other for such hold-ups.

Pointing the finger at his Ghanaian counterparts, an Ivorian official complained that Ghana insisted on closing the border at 6.30pm every day. But 500m away, a Ghanaian immigration officer retorted that his country’s laws were “perfect”, adding that “the difficulties are with our neighbours”.

Mr Oppong and his frustrated colleagues said there was a disagreement over how much duty should be paid as they crossed from Ivory Coast. Yet their cargo was hardly contentious — all they were transporting was empty milk cartons.

“Hopefully we’ll get it sorted tomorrow,” he said. “But we’re luckier than some people. Some cargo is delayed here for a month.”

Such problems are common across Africa as poor logistics, bureaucratic bottlenecks, decaying infrastructure and corruption are blamed for stymieing trade across the continent’s borders. Ivory Coast and Ghana are both members of the Economic Community of West African States (Ecowas), which allows for duty-free shipments for products made in the 15-country bloc. That Mr Oppong and his fellow drivers were held up demonstrates the challenges for politicians and businesspeople trying to deepen economic ties.

The hope is that such issues will soon be consigned to history following the signing last month of a landmark continent-wide free trade agreement. The African Continental Free Trade Area, which was signed by 44 African leaders, aims to reduce 90 per cent of tariffs to zero from the current average of 6.1 per cent.

“We now have the construction for meaningful intercontinental trade,” Nana Akufo-Addo, Ghana’s president, said after the deal was signed. “An increase in trade is the surest way to develop fruitful relations between our countries, enhance development and attain prosperity.”

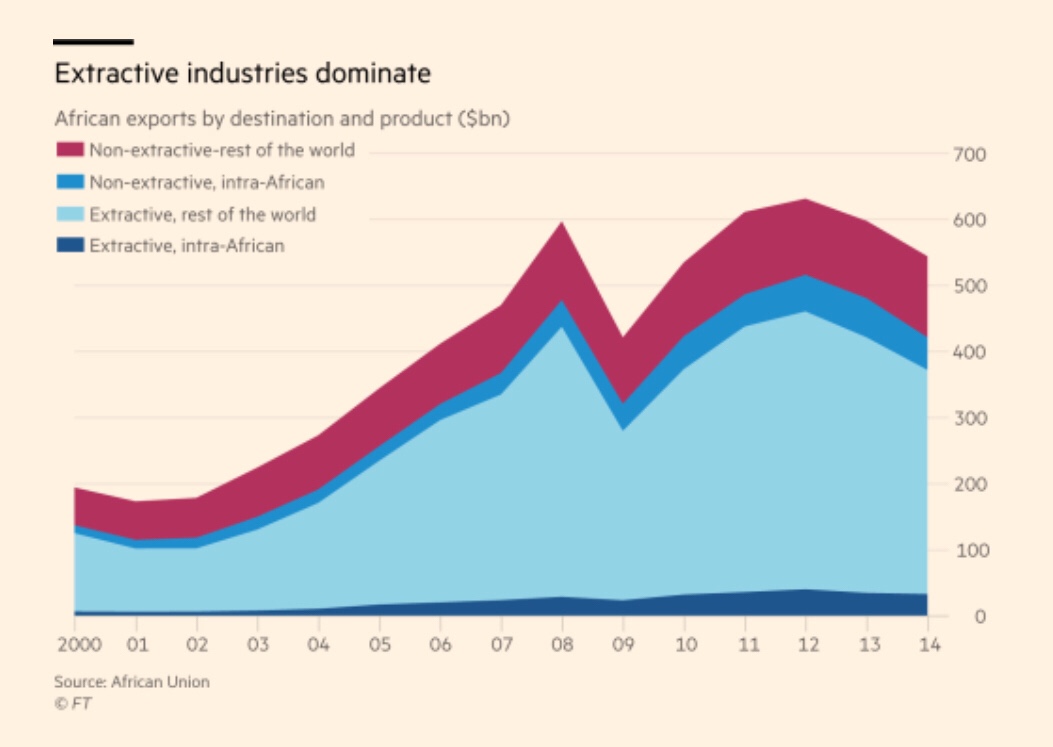

There is big potential, analysts say. Africa boasts a market of 1.2bn people and a combined economic output of $2.5tn, according to the African Union. And the population is expected to double by 2050, the UN says. But intra-African trade accounts for only about $170bn, or 18 per cent, of the continent’s total annual formal commerce, according to the African Export-Import Bank. This compares with about 68 per cent for the EU.

“An increase in trade is the surest way to develop fruitful relations between our countries, enhance development and attain prosperity.”

The UN’s economic commission on Africa estimated that if the new trade deal was fully implemented intra-African trade would swell at least 50 per cent within five years.

But translating the leaders’ dreams into reality will be difficult. The continent’s two largest economies, Nigeria and South Africa, are among 11 governments that have refused to sign the agreement. Their leaders’ claims that they need to protect nascent domestic industries illustrate how national interests can hamper greater continental integration.

Parfait Kouassi, an Ivorian businessman and deputy chairman of the country’s chamber of commerce, said he was “very sceptical” about the trade deal’s short-term prospects because of “so many officials’ narrow-minded thinking”. He recently wanted to build a medicine factory in Benin but “it just couldn’t happen because of the bureaucracy”.

“If I want to export pharmaceuticals from here to [neighbouring] Burkina Faso I have to export them first to France,” Mr Kouassi said.

Arancha González, executive director of the International Trade Centre, an agency mandated by the UN and World Trade Organization, acknowledged that implementation would be challenging, partly because Africa is “55 markets that are the product of history rather than the product of enlightened thinking”.

“The biggest obstacle is structures of power in countries that rely too much on the status quo than opening up,” she said. “Trade is disorganised in many countries because it’s designed to finance activities that do not promote the free flow of goods and services.”

Still, there are examples that show that regional trade can work if the right conditions are put in place.

Trade flows between Kenya and Uganda have been transformed since a “one-stop” border post was established in Busia, two towns of the same name straddling the frontier of the two east Africa nations, in 2016.

Officials from the two countries sit next to each other to eliminate duplication of services. “When I first arrived at the border six years ago, clearance times were sometimes up to six days,” said Michael Akiyo, a senior Ugandan customs official. “Now it’s usually about 20 minutes, or in a worst-case scenario two hours.”

Truck drivers waiting at the border agree. And both Kenyan and Ugandan revenue authorities say their income from the border post has increased about 50 per cent since it opened, with the vast majority attributed to greater efficiency.

“When I first arrived at the border six years ago, clearance times were sometimes up to six days. Now it’s usually about 20 minutes, or in a worst-case scenario two hours.”

Perhaps the biggest revolution has been in the informal sector, which accounts for three-quarters of employment in sub-Saharan Africa. Benedict Oramah, the president of the African Export-Import Bank, estimated cross-border informal trade was worth as much as $60bn a year across the continent.

Special facilities, including warehouses and offices for associations run by local volunteers, have been incorporated into the border post so traders, many of whom are carrying goods worth only a few hundred dollars, can be processed rapidly.

“I used to smuggle the vast majority of my goods,” said Stella Rose, who added that she had been trading across the border for 26 years. “But now the fines for getting caught have risen and the cost of using the formal border post has fallen by two-thirds so I cross properly.”

Volunteers at the border said 26,000 informal traders have crossed in the past year, almost double the number a year ago, and they expected similar growth this year. But free trade advocates hope such success stories will ripple rapidly across the continent. However, the east Africa experience is an exception, and analysts warn that greaterAfrica-wide integration will be a long and difficult process.

“I used to smuggle the vast majority of my goods, but now the fines for getting caught have risen and the cost of using the formal border post has fallen by two-thirds so I cross properly.”

“The tide will turn in favour of free trade eventually,” Mr Kouassi said. “But it will be more than 10 years because [the protectionist states] are afraid of us more developed countries.”

Source: F T, J.Aglionby

You must be logged in to post a comment.