Africa has a new free trade area. This is what you need to know

African leaders have just signed a framework establishing the African Continental Free Trade Area, the largest free trde agreement since the creation of the World Trade Organisation.

The free trade area aims to create a single market for goods and services in Africa. By 2030 the market size is expected to include 1.7 billion people with over USD$ 6.7 trillion of cumulative consumer and business spending – that’s if all African countries have joined the free trade area by then. Ten countries, including Nigeria, have yet to sign up.

The goal is to create a single continental market for goods and services, with free movement of business persons and investments.

The agreement has the potential to deliver a great deal for countries on the continent. The hope is that the trade deal will trigger a virtuous cycle of more intra African trade, which in turn will drive the structural transformation of economies – the transition from low productivity and labour intensive activities to higher productivity and skills intensive industrial and service activities – which in turn will produce better paid jobs and make an impact on poverty.

But signing the agreement is only the beginning. For it to come into force, 22 countries must ratify it. Their national legislative bodies must approve and sanction the framework formally, showing full commitment to its implementation. Niger President Issoufou Mahamadou, who has been championing the process, aims to have the ratification process completed by January 2019.

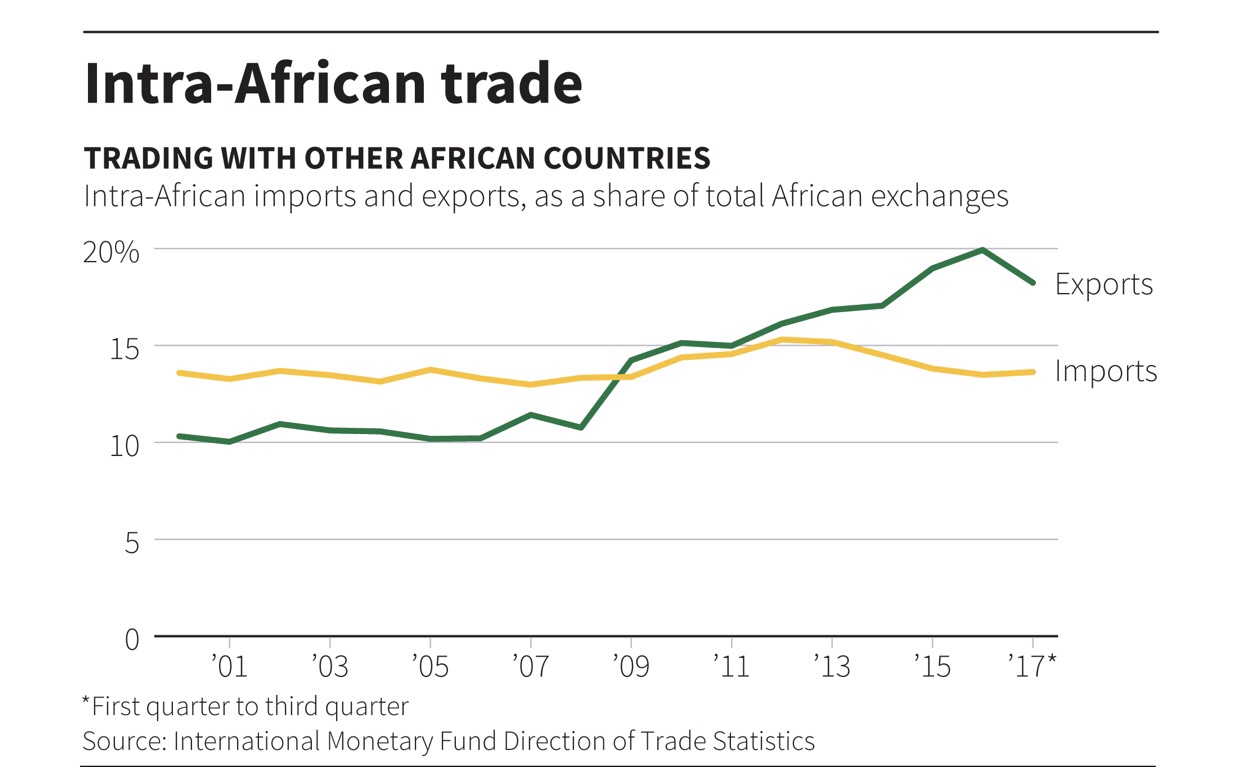

Some studies have shown that by creating a pan-African market, intra-Africa trade could increase by about 52% by 2022. Better market access creates economies of scale. Combined with appropriate industrial policies, this contributes to a diversified industrial sector and growth in manufacturing value added.

Manufacturing represents only about 10% of total GDP in Africa on average. This falls well below other developing regions. A successful continental free trade area could reduce this gap. And a bigger manufacturing sector will mean more well-paid jobs, especially for young people. This in turn will help poverty alleviation.

Industrial development, and with it, more jobs, is desperately needed in Africa. Industry represents one-quarter to one-third of total creation in other regions of the world. And a young person in Africa is twice as likely to be umeployed when he or she becomes an adult. This is a particularly stressful situation given that over 70% of sub-Saharan Africa’s population is below age 30.

In addition, 7% of Africa’s youth live on less than $2 per day.

The continental free trade area is expected to offer substantial opportunities for industrialisation, diversification, and high-skilled employment in Africa.

The single continental market will offer the opportunity to accelerate the manufacture and intra-African trade of value-added products, moving from commodity based economies and exports to economic diversification and high-value exports.

But, to increase the impact of the trade deal, industrial policies must be put in place. These must focus on productivity, competition, diversification, and economic complexity.

In other words, governments must create enabling conditions to ensure that productivity is raised to international competitiveness standards. The goal must be to ensure that the products manufactured in African countries are competitively traded on the continent and abroad, and to diversify the range and sophistication of products and services.

Data shows that the most economically diverse countries are also the most successful.

In fact, diversification is critical as “countries that are able to sustain a diverse range of productive know-how, including sophisticated, unique know-how, are able to produce a wide diversity of goods, including complex products that few other countries can make.

Diverse African economies such as South Africa and Egypt, are likely to be the drivers of the free trade area, and are likely to benefit from it the most. These countries will find a large continental market for their manufactured products. They will also use their know-how and dense industrial landscape to develop innovative products and respond to market demand.

But the agreement on its own won’t deliver results. Governments must put in place policies that drive industrial development, particularly manufacturing. Five key ones stand out:

Human capital: A strong manufacturing sector needs capable, healthy, and skilled workers. Policymakers should adjust curriculum to ensure that skills are adapted to the market. And there must be a special focus on young people. Curriculum must focus on skills and building capacity for entrepreneurship and self-employment. This should involve business training at an early age and skills upgrading at an advanced one. This should go hand in hand with promoting science, technology, engineering, entrepreneurship and mathematics as well as vocational and on-the-job training.

Policymakers should also favour the migration of highly skilled workers across the continent.

Cost: Policymakers must bring down the cost of doing business. The barriers include energy, access to roads and ports, security, financing, bureaucratic restrictions, corruption, dispute settlement and property rights.

Supply network: Industries are more likely to evolve if competitive networks exist. Policymakers should ease trade restrictions and integrate regional trade networks. In particular, barriers for small and medium-size businesses should be lifted.

Domestic demand: Policymakers should offer tax incentives to firms to unlock job creation, and to increase individual and household incomes. Higher purchasing power for households will increase the size of the domestic market.

Resources: Manufacturing requires heavy investment. This should be driven by the private sector. Policymakers should facilitate access to finance, especially for small and medium enterprises. And to attract foreign direct investment, policymakers should address perceptions of poor risk perception. This invariably scares off potential investors or sets excessive returns expectations.

Source: WEF