Most people, whether rich or poor, are totally wrong about poverty

The percentage of people living in extreme poverty around the world has fallen by more than half over the past three decades. But polls show that most people are not only ignorant of this fact, but believe that poverty has increased. This column explores progress towards ending global poverty by 2030, the first of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals. Poverty figures have fallen around the world since 1990, and there is a broad consensus on the policies needed for further reductions. Eradicating global poverty is achievable, but it is dependent on global and domestic political cooperation.

“Did you know that, in the past 30 years, the percentage of people in the world who live in extreme poverty has decreased by more than half?”

In 2014, 84% of Americans who were asked this question were unaware of such declines in global extreme poverty. In fact, 67% of adult respondents thought global poverty had been on the rise over the past three decades. Unsurprisingly, 68% did not believe it would be possible to end extreme global poverty within the next 25 years (Todd 2014).

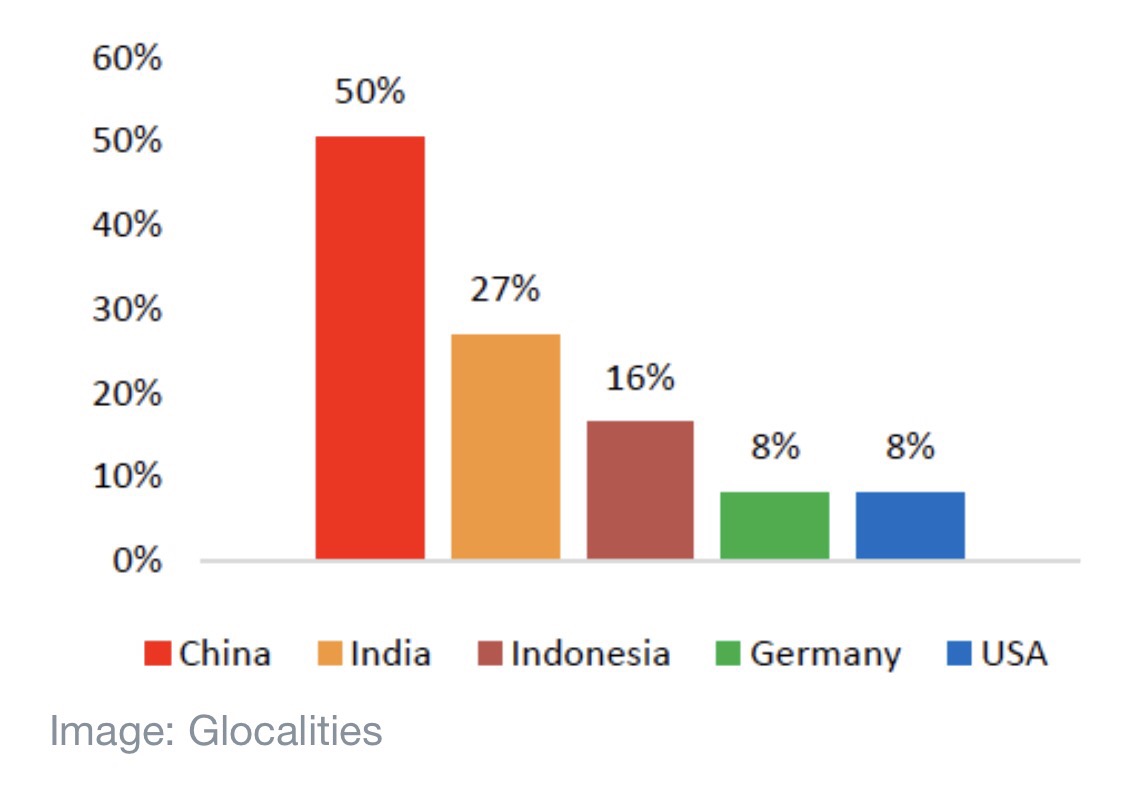

A recent study analysing the public awareness around the world of the Sustainable Development Goals confirmed that this widespread ignorance is not a US anomaly (Lampert and Papadongonas 2016).1 A significant majority of respondents from several countries, both developing and developed, are unaware of this achievement (see Figure 1). Interestingly, Chinese citizens appear much better informed about global poverty trends than those of the US or Germany.

Figure 1. Share of people who believe that extreme global poverty has decreased in the last 20 years

But this is just what adults report. On 17 October – the International Day for the Eradication of Poverty – a poll of about 150 college students from the Washington metropolitan area were invited to the World Bank and showed more encouraging results (World Bank 2016a). Two thirds correctly responded that global extreme poverty has been reduced. Yet, more than half of those didn’t think the decline had been substantial. Even less auspicious, only four out of ten thought that extreme poverty could be ended by 2030 (World Bank 2016a).

It is tempting to engross ourselves in a discussion of why so many people know so little about this incredible accomplishment, dubbed by the New York Times’ Nicholas Kristof “the best news you don’t know” (2016). Keeping speculations aside, we simply express our bewilderment at how widespread these wrong perceptions about today’s number one global development challenge are, especially within a hyper-connected and social media-addicted world.

The second part of this story is equally fascinating. Will global poverty end by 2030? We cannot really say for sure, and pretending to have a definite answer may seem ludicrous when we can’t even confidently estimate real-time poverty numbers. Indeed, our latest estimates in 2016 refer to global poverty in 2013 – a three-year lag.

However, there are several reasons to be optimistic about ending poverty by 2030.

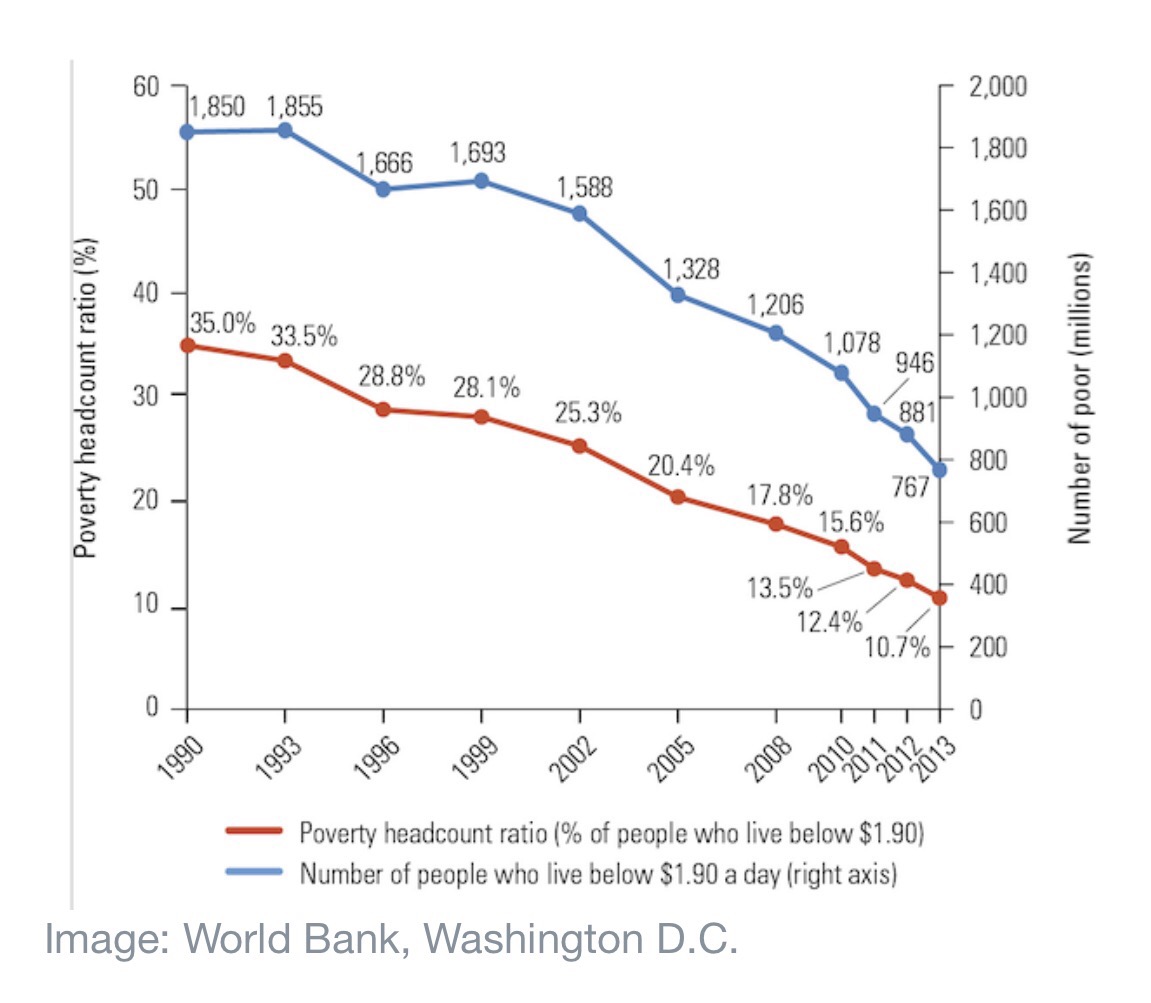

The new Poverty and Shared Prosperity Report 2016 launched this October by the World Bank explains why (World Bank 2016b). The figure below shows that the number of extremely poor people worldwide – measured by the very low $1.90 a day standard – has fallen by 1.1 billion people over the last two and a half decades, a period in which the global population grew by almost 2 billion (see Figure 2). This is true for all regions in the world without exception, from relatively richer Eastern Europe and Latin America to poorer Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. True, each region has reduced their poverty numbers at different paces. But the numbers leave little room for doubt – extreme poverty has been effectively and dramatically reduced.

Figure 2. The global poverty headcount ratio and the number of the extreme poor, 1990-2013

The second reason to be optimistic is that we know a good deal about how to reduce extreme poverty. The slashing of extreme poverty worldwide is not a random phenomenon. Leaving ideological views on the role of globalisation in this decline aside, the astonishing reduction in global poverty has been steadfast since the moment we have been able to track it confidently with household surveys, which began around 1990. The unwavering decline has taken place through economic booms but has also weathered global crises, most notoriously the Great Recession in 2007-08. For the record, the only exception was the Asian crisis in the late 1990s, when global poverty actually increased in numbers and rates.

Summarising decades of research on poverty reduction is beyond the scope of this column. Let’s simply say that there is a broad consensus around a set of policies that allow countries to grow inclusively:

– Invest in the human capital of citizens and the infrastructure of countries, to make both people and economies competitive and diversified;Protect populations from risks that threaten to reverse hard fought and won prosperity gains – this includes everything from illness to unemployment, droughts to cyclones.

– While the exact recipe may change depending on a given country’s circumstances, the strategies mentioned above are common ingredients in most successful cases of poverty reduction. Strategies eloquently coined by the World Bank as “grow, invest, and insure” (Gill et al. 2016).

The third reason for optimism is that eliminating extreme poverty may not be as expensive as one may think. The true cost is probably impossible to estimate with precision, but a simple back of the envelope calculation of the total income needed to close the gap to the minimum standard of living ($1.90 per day) for the world’s current extreme poor produces a perplexingly low bill – 0.15% of global GDP, or $150 billion a year. This bulk figure bluntly ignores that the real world involves administrative costs, political will, the need to properly identify and target the poor, and the challenge of sustaining millions out of poverty in the future. But this figure busts the myth that ending poverty is a chimera that troubled economies today cannot afford. Our back of the envelope figure is arguably half of the tax revenue estimated to be lost every year to tax havens. It is also less than half of the money lost in gambling every year in just ten countries around the world (Aziz 2014). We can all do the maths.

But as with any prediction into a distant future, one ought to be very cautious. If the world were to reduce poverty at the same pace it currently does, poverty would end well before 2030. Sadly, making such a linear extrapolation is naïve and misleading. We cannot bank anymore on the rapid reduction of poverty that came from the spectacular performance of China and other emerging populous countries. Simply put, their success will make these countries run out of extreme poor soon – again, and let’s insist on this, measured by earning less than $1.90 a day. China and Indonesia’s latest numbers are about 25 million each. India, however, still hosts 217 million poor and its ability to reduce this number will be instrumental in reaching the goal of ending global poverty. But, more generally, it is from the corners of the world ridden by fragility, conflict, poor governance, undiversified economies, vulnerability to climate change, and a long list of other socioeconomic and political woes that the last mile in reducing poverty must be walked through. And trusting it all to strong economic growth in these countries will simply not do the trick. The world continues to show symptoms of a protracted economic pneumonia, with low-income countries now facing more challenging circumstances (even after displaying considerable resilience during the Global Crisis of 2008-09). Since the end of the commodity super-cycle in 2014, growth rates have come down across the developing world and there is little reason to expect a quick turnaround. This is why a better distribution of the benefits of growth becomes key to achieving the goal of eliminating poverty by 2030.

So, we do not know for sure if poverty will be eliminated by 2030. After all, what do we know for certain these days, anyway? President Obama has set the goal of sending humans to Mars by the 2030s and returning them safely to Earth. Will the world achieve such a feat? Or end poverty by 2030? In the case of poverty we do know a great deal about how to do it. Concretely, we already know the policies that are needed to bring the world to the end of extreme poverty, if only global and domestic politics would let them work. And we also know what challenges lay ahead and where. The only thing we seem not to know is that we do know all of this. And as Winston Churchill once warned, “those who fail to learn from history…”

Authors’ note: The views expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the institutions with which they are affiliated.

References

Aziz, J (2014) “How did Americans manage to lose $119 billion gambling last year?”, The Week, 5 February.

Gill, I, A Revenga and C Zeballos (2016) “Grow, invest, insure: A game plan to end poverty by 2030”, World Bank, mimeograph.

Kristof, N (2016) “The best news you don’t know”, New York Times, 22 September.

Lampert, M and P Papadongonas (2016) “Towards 2030 without poverty: Increasing knowledge of progress made and opportunities for engaging frontrunners in the world population with the global goals”, Glocalities, Amsterdam.

Todd, S (2014) Hope rising: How Christians can end extreme poverty in this generation, Nelson Books, Nashville, Tennessee;

World Bank (2016a) End Poverty Day 2016 Staff Event with Local University Students.

World Bank (2016b) Poverty and Shared Prosperity Report 2016: Taking on Inequality.

Endnotes

[1] A more comprehensive – and difficult – quiz testing your knowledge on global poverty can be found here.

Written by

Jose Cuesta, Senior Economist, World Bank

Christoph Lakner, Economist in the Poverty and Equity Global Practice, The World Bank.

Mario Negre, Senior uEconomist, World Bank Development Research Group

This article was published in collaboration with VoxEU.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Source: WEF

You must be logged in to post a comment.