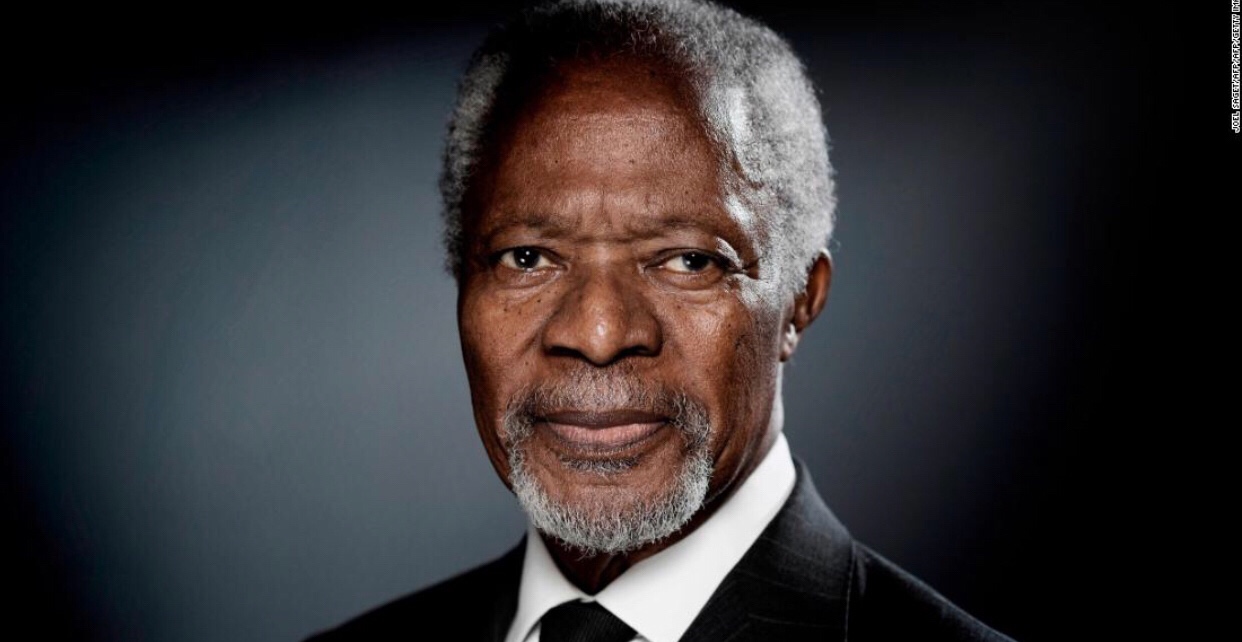

There are not many people that becomes legends in their own time. Someone has said there are maybe 2-3 in every generation.

I think that one of them left us today.

Today we mourn the loss of a great man, a leader, and a visionary – former UN Secretary General, Kofi Annan.

Kofi Annan, the first black African to lead the United Nations, has died at age 80. He served as Secretary-General at a time when worries about the Cold War were replaced by threats of global terrorism, and his efforts to combat those threats and secure a more peaceful world brought him the Nobel Peace Prize.

Kofi had a connection to Sweden being married to his Swedish wife Nane.

When He enetered a room you could feel thst he had that energy, integrity and charisma that only great leaders have. I have had the honor to experience that myself.

Jens Stoltenberg, Head of NATO, tweeted that the world had lost one of its giants. “His warmth should never be mistaken for weakness,” he said. “Annan showed that one can be a great humanitarian and a strong leader at the same time.”

Annan, who was born in Ghana in 1938, served as the seventh UN Secretary-General, from 1997 to 2006, and was the first to rise from within the ranks of the United Nations staff.

He had also been a member, since 2007, of The Elders, a humanitarian group of a dozen leaders and activists of worldwide stature formed by Nelson Mandela. In 2013, Annan became its chairman.

The present Secretary-General Antionio Guterres expressed the admirstion and gratefulness for Kofi Annans lifelong service to the organtization.

“In these turbulent and trying times, he never stopped working to give life to the values of the United Nations Charter. His legacy will remain a true inspiration for all of usd”

Kofi Annan was UN. He lived and served his life in the organization and for the people of the world. For us.

Maersk and IBM have introduced their global blockchain solution TradeLens, with 94 organizations already participating. The companies announced their joint venture in January this year after collaborating on the concept since 2016.

Early adopters include more than 20 port and terminal operators across the globe, including PSA Singapore, International Container Terminal Services Inc, Patrick Terminals, Modern Terminals in Hong Kong, Port of Halifax, Port of Rotterdam, Port of Bilbao, PortConnect, PortBase and terminal operators Holt Logistics at the Port of Philadelphia. They join the global APM Terminals’ network in piloting the solution at over 230 marine gateways worldwide.

Pacific International Lines has joined Maersk Line and Hamburg Süd as global container carriers participating. Customs authorities in the Netherlands, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, Australia and Peru are participating, along with customs brokers Ransa and Güler & Dinamik.

Participation among beneficial cargo owners has grown to include Torre Blanca / Camposol and Umit Bisiklet. Freight forwarders, transportation and logistics companies including Agility, CEVA Logistics, DAMCO, Kotahi, PLH Trucking Company, Ancotrans and WorldWide Alliance.

TradeLens uses IBM Blockchain technology built on open standards to establish a single shared view of a transaction without compromising details, privacy or confidentiality. Shippers, shipping lines, freight forwarders, port and terminal operators, inland transportation and customs authorities can interact via real-time access to shipping data ad shipping documents, including IoT and sensor data ranging from temperature control to container weight.

Using blockchain smart contracts, TradeLens enables digital collaboration across the multiple parties involved in international trade. The trade document module, released under a beta program and called ClearWay, enables importers/exporters, customs brokers, trusted third parties such as Customs, other government agencies, and NGOs to collaborate in cross-organizational business processes and information exchanges, all backed by a secure, non-repudiable audit trail.

During a 12-month trial, Maersk and IBM worked with dozens of partners to identify opportunities to prevent delays caused by documentation errors and information delays. One example demonstrated how TradeLens can reduce the transit time of a shipment of packaging materials to a production line in the U.S. by 40 percent, avoiding thousands of dollars in cost.

Through better visibility and more efficient means of communicating, some supply chain participants estimate they could reduce the steps taken to answer basic operational questions such as “where is my container” from 10 steps and five people to, with TradeLens, one step and one person.

More than 154 million shipping events have been captured on the platform, including data such as arrival times of vessels and container “gate-in,” and documents such as customs releases, commercial invoices and bills of lading. This data is growing at a rate of close to one million events per day.

TradeLens is expected to be fully commercially available by the end of this year.

Source: Martine Executive/Mike Poverello

The Foreign Secretary, Jeremy Hunt, says the chances of a “no deal” Brexit are “increasing by the day”. The International Trade Secretary, Liam Fox, has been quoted as saying the chances of no deal are “60-40”. And the governor of the Bank of England, Mark Carney, says they are “uncomfortably high.”

There seems to be a pattern developing here.

Recent debate about no deal – which would mean the UK leaving the European Union (EU) next year without any withdrawal agreement – has focused on the fact that the UK would automatically fall back on World Trade Organization (WTO) trade rules. Those rules would apply automatically to UK trade with the EU and other countries with which the EU has free-trade deals.

So what would WTO rules mean in practice?

First, the basics. What is the WTO?

The WTO is the place where countries negotiate the rules of international trade – 164 countries are members and, if they don’t have free trade agreements with each other, they trade under “WTO rules”.

Which are?

Every WTO member has a list of tariffs (taxes on imports of goods) and quotas (limits on the number of goods) that they apply to other countries. These are known as their WTO schedules.

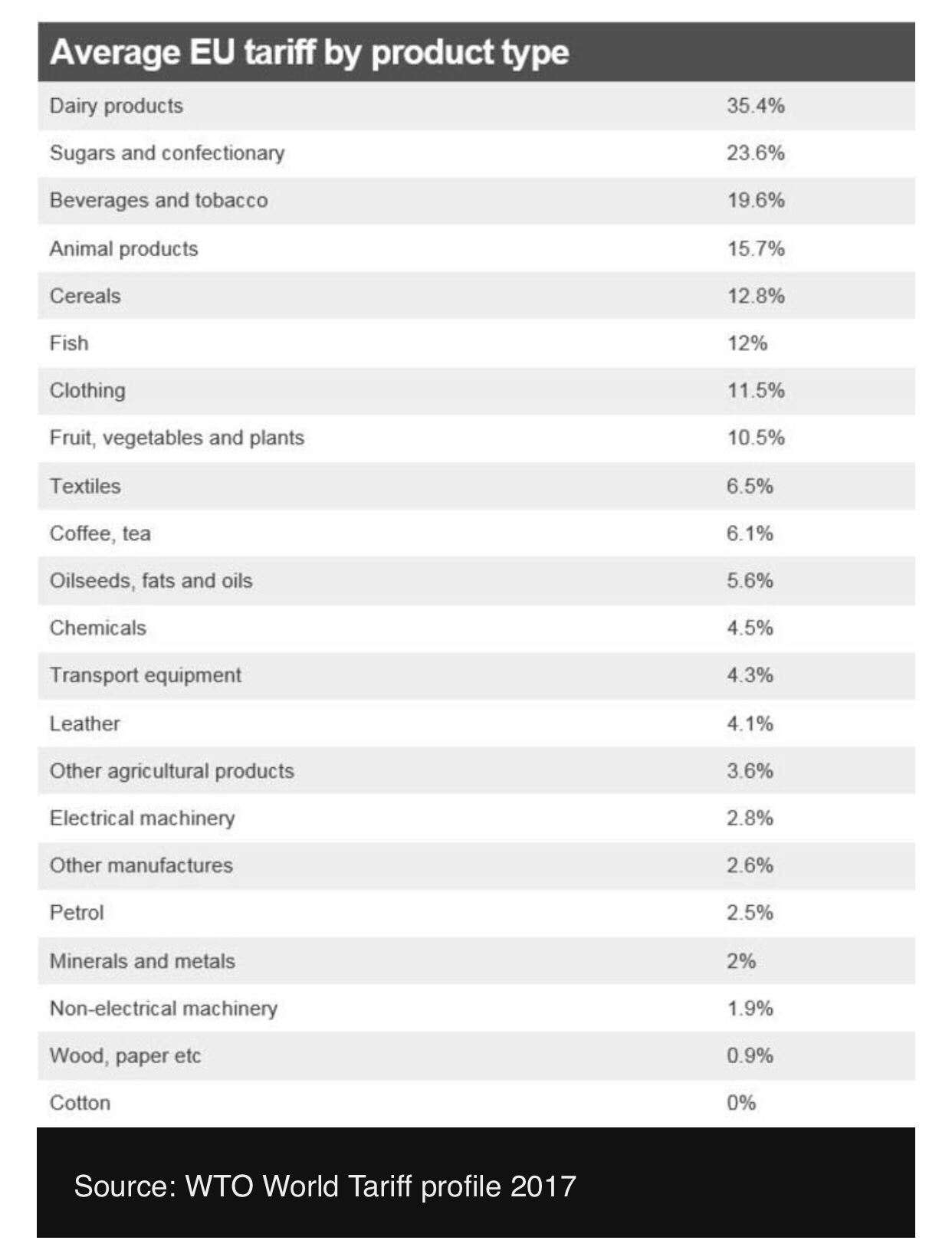

The average EU tariff is pretty low (about 2.6% for non-agricultural products)- but, in some sectors, tariffs can be quite high.

Under WTO rules, cars and car parts, for example, would be taxed at 10% every time they crossed the UK-EU border. And agricultural tariffs are significantly higher, rising to an average of over 35% for dairy products.

After Brexit, the UK could choose to lower tariffs or waive them altogether, in an attempt to stimulate free trade. That could mean some cheaper products coming into the country for consumers but it could also risk driving some UK producers out of business.

It’s important to remember that, under the WTO’s “most favoured nation” rules, the UK couldn’t lower tariffs for the EU, or any specific country, alone. It would have to treat every other WTO member around the world in the same way.

What about other checks and costs?

These are what are known as “non-tariff barriers” and include things such as product standards and safety regulations. Once the UK is no longer part of the EU, there needs to be a system for mutually recognising each other’s standards and regulations. Under a no deal Brexit this may not happen, at least not immediately.

You can argue that it might seem unreasonable if the EU was to go from imposing no checks on UK products at borders the day before Brexit, to insisting on all sorts of checks one day later, even though the UK hadn’t changed any of its rules and regulations.

Doesn’t the UK already trade with many countries on WTO rules?

Yes it does, as part of the EU.

Examples include the United States and China, Brazil and Australia. In fact, it’s any country with which the EU (and therefore the UK) has not signed a free trade agreement. That’s when WTO rules kick in.

But it’s more complicated than that. Those big economies don’t just rely on WTO rules – they also have a series of bilateral agreements with the EU on top of that.

The US, for example, has at leadt twebty agreements with the EU that help regulate specific areas of trade, covering everything from wine and bananas to insurance and energy-efficiency labelling.

In the event of a no deal Brexit, (and an abrupt change in relations), the UK could well have no such deals in place and would be in new territory. Both sides would make efforts to introduce some stopgap measures to keep their economies moving but a last-minute breakdown in negotiations would prove very difficult.

It’s also worth remembering that 44% of all UK exports in 2017 went to the European Union on free trade terms, as part of the single market. That’s down from 55% in 2006 but the EU is still by far the largest UK export market.

“Clearly this is not going to be a situation where all trade stops and there is collapse in terms of the economy as a whole,” said the WTO’s director general, Roberto Azevedo, when he was asked in a BBC interview last year about the potential effect of a hard Brexit on the UK and European economies.

“But it’s not going to be a walk in the park. It’s not like nothing will happen. There will be an impact. The tendency is that prices will go up of course, [because] you have to absorb the cost of that disruption.”

Some people say it won’t be a problem

Yes, some supporters of Brexit argue that no deal is the best way forward, because it would allow the UK to pursue an independent trade policy immediately – to go off and start signing its own trade deals.

That is not the government’s view or the EU’s view, nor is it the view of the vast majority of businesses.

A number of recent articles by supporters of Brexit have made reference to the WTO:s Trade Facilitation Agreement (TFA), which came into force in 2017, arguing that it obliges the EU to treat the UK fairly.

But that doesn’t stand up to scrutiny.

The TFA is aimed primarily at less developed countries and it seeks to encourage transparency and streamline bureaucratic procedures.

It does mean the EU cannot discriminate against the UK but it does not mean the UK can expect to be treated in the same way that it is now.

The UK would be treated like any other third country – and in the absence of any trade agreement, that means tariffs and border checks.

Will the UK have to re-join the WTO after Brexit?

No, it is already a member in its own right.

But it will have to agree a new list of tariff schedules once it is no longer part of the EU.

Like many other parts of the Brexit negotiations, that could be harder than it sounds.

The UK has already submitted documents to the WTO in Geneva, which say that it wants to make a few technical changes to its current commitments as an EU member but otherwise leave them unchanged.

But other countries will want to make sure they are no worse off than they are now after Brexit, while the UK is seeking the same schedules even though after leaving the EU it will represent a much smaller market.

One problem for both the UK and the EU surrounds proposals they have submitted for splitting up their current quotas after Brexit, for the import of sensitive agricultural products such as beef, lamb and sugar from elsewhere in the world. These proposals have already attracted complaints from other countries, including the United States.

And time is running rather short to complete what are always complex negotiations, in which every country will stick up for its own interests.

With a bit of goodwill, the UK hopes it will be able to resolve the debate about WTO schedules. But one of the dangers of a no deal Brexit is that there might not be much goodwill around, especially if it meant that the UK was refusing to pay the more than £39bn it has provisionally agreed it owes the EU as it leaves.

So this is a technical issue, but politics will also play a big role.

Source: Chris Morris, BBC

You must be logged in to post a comment.