The true cost of corruption is higher than you might realise

I was once in a meeting where the former UN Secretary General Kofi Annan said ‘Corruption is the enemy of poor’.

I have always remembered those words. Kofi Annan is certainly one of the most impressive leaders I have ever meet. But these words always stuck with me and has had a great impact on the work I have carried out in the area of capacity building, Customs reform and modernization.

As Director of the World Customs Organization (WCO) I was respensible for Integrity and Anti-Corruption programmes of the organization and in the 182 member countries. We did a number of successful initiatives in all regions of the world during those years and the work has continued.

As a fundamental tool for revenue collection, Customs has always been accused of being more or less corrupt. I will argue that this today is a myth from the past. There are certainly still huge integrity and corruption challenges in some countries and all countries always have a the problem of corruption, but it should also be acknowledged that we have come a long way.

The moment we realized that corruption in Customs or at the Borders is not a Customs problem but a larger society problem. It needs to be addressed as a society problem. There need to be a political will and 100% support from above to fight corruption. If the overall environment does not allow integrity then there will be no integrity. What we found out is that the medication for this disease is a multilear approach with; leadership, communication, “carrot & stick” policies, controls/inspections, risk filters, independent audits and maybe most important automation – building away use of and access to cash payments. To mention a few measures.

Most important to say is that anti-corruption is not a project but an on-going daily effort. There are always risks for corruption and it is everywhere, always. So this is how we need to fight it.

One time in WCO I invited the #1-3 of the highest ranked countries on Transparency Internationals Corruption Perception Index. It was Finland, Sweden and Netherlands at the time. These countries transparently displayed not only their systematic work and systems against corruption, but they also told openly about their hundreds of found and mitigated cases every year.

Many developing countries of the membership afterwards described this session as breakthrough since they felt for the first time that the western world was sharing and not pointing finger at poor countries, “saying this is your problem” – while it is not. Corruption is always our problem and corruption is always the enemy of the poor.

This is also why I enjoyed the article from the WEF (also referring to work by the IMF) her below showing corruption consequences. Read it. There are many interesting perspectives described.

No country is immune to corruption. The abuse of public office for private gain erodes people’s trust in government and institutions, makes public policies less effective and fair, and siphons taxpayers’ money away from schools, roads, and hospitals.

While the wasted money is important, the cost is about much more. Corruption corrodes the government’s ability to help grow the economy in a way that benefits all citizens.

But the political will to build strong and transparent institutions can turn the tide against corruption. In our new Fiscal Monitor, we shine a light on fiscal institutions and policies, like tax administration or procurement practices, and show how they can fight corruption.

“Political will can turn the tide against corruption.”

We analyze more than 180 countries and find that more corrupt countries collect fewer taxes, as people pay bribes to avoid them, including through tax loopholes designed in exchange for kickbacks. Also, when taxpayers believe their governments are corrupt, they are more likely to evade paying taxes.

We show that overall, the least corrupt governments collect 4 percent of GDP more in tax revenues than countries at the same level of economic development with the highest levels of corruption.

A few countries’ reforms generated even higher revenues. Georgia, for example, reduced corruption significantly and tax revenues more than doubled, rising by 13 percentage points of GDP between 2003 and 2008. Rwanda’s reforms to fight corruption since the mid-1990s bore fruit, and tax revenues increased by 6 percentage points of GDP.

Corruption also prevents people from benefiting fully from the wealth created by their country’s natural resources. Because the exploration of oil or mining generates huge profits, it creates strong incentives for corruption. Our research shows that resource-rich countries, on average, have weaker institutions and higher corruption.

The Fiscal Monitor shows that countries with lower levels of perceived corruption have significantly less waste in public investment projects. We estimate that the most corrupt emerging market economies waste twice as much money as the least corrupt ones.

Governments waste taxpayers’ money when they spend it on cost overruns due to kickbacks or bid rigging in public procurement. So, when a country is less corrupt, it invests money more efficiently and fairly.

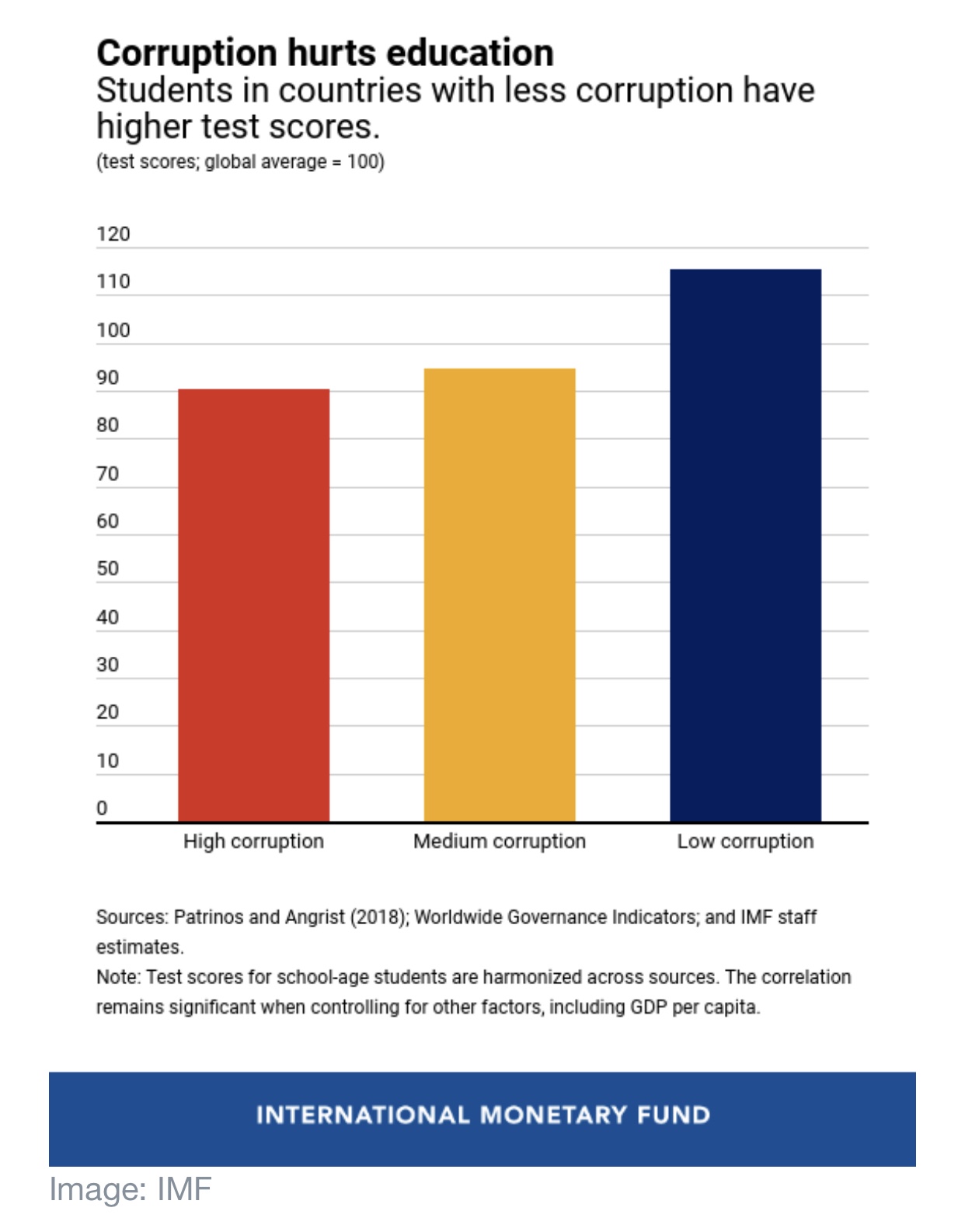

Corruption also distorts government priorities. For example, among low-income countries, the share of the budget dedicated to education and health is one-third lower in more corrupt countries. It also impacts the effectiveness of social spending. In more corrupt countries school-age students have lower test scores.

Corruption is also a problem in state-owned enterprises, such as some countries’ oil companies, and public utilities like electric and water companies. Our analysis suggests that these enterprises are less efficient in countries with high levels of corruption.

Where there is political will, there is a way

Fighting corruption requires political will to create strong fiscal institutions that promote integrity and accountability throughout the public sector.

Based on the research, here are some lessons for countries to help them build effective institutions that curb vulnerabilities to corruption:

Invest in high levels of transparency and independent external scrutiny. This allows audit agencies and the public at large to provide effective oversight. For example, Colombia, Costa Rica, and Paraguay are using an online platform that allows citizens to monitor the physical and financial progress of investment projects. Norway has developed a high standard of transparency to manage its natural resources. Our analysis also shows that a free press enhances the benefits of fiscal transparency. In Brazil, the results of audits impacted the reelection prospects of officials suspected of misuse of public money, but the impact was greater in areas with local radio stations.

Reform institutions. The chances for success are greater when countries design reforms to tackle corruption from all angles. For example, reforms to tax administration will have a greater payoff if tax laws are simpler and they reduce officials’ scope for discretion. To help countries, the IMF has built comprehensive diagnostics on the quality of fiscal institutions, including public investment management, revenue administration, and fiscal transparency.

Build a professional civil service. Transparent, merit-based hiring and pay reduce the opportunities for corruption. The heads of agencies, ministries, and public enterprises must promote ethical behavior by setting a clear tone at the top.

Sources: WEF, IMF

You must be logged in to post a comment.