Brexit: What is the ‘no deal’ WTO option?

The Foreign Secretary, Jeremy Hunt, says the chances of a “no deal” Brexit are “increasing by the day”. The International Trade Secretary, Liam Fox, has been quoted as saying the chances of no deal are “60-40”. And the governor of the Bank of England, Mark Carney, says they are “uncomfortably high.”

There seems to be a pattern developing here.

Recent debate about no deal – which would mean the UK leaving the European Union (EU) next year without any withdrawal agreement – has focused on the fact that the UK would automatically fall back on World Trade Organization (WTO) trade rules. Those rules would apply automatically to UK trade with the EU and other countries with which the EU has free-trade deals.

So what would WTO rules mean in practice?

First, the basics. What is the WTO?

The WTO is the place where countries negotiate the rules of international trade – 164 countries are members and, if they don’t have free trade agreements with each other, they trade under “WTO rules”.

Which are?

Every WTO member has a list of tariffs (taxes on imports of goods) and quotas (limits on the number of goods) that they apply to other countries. These are known as their WTO schedules.

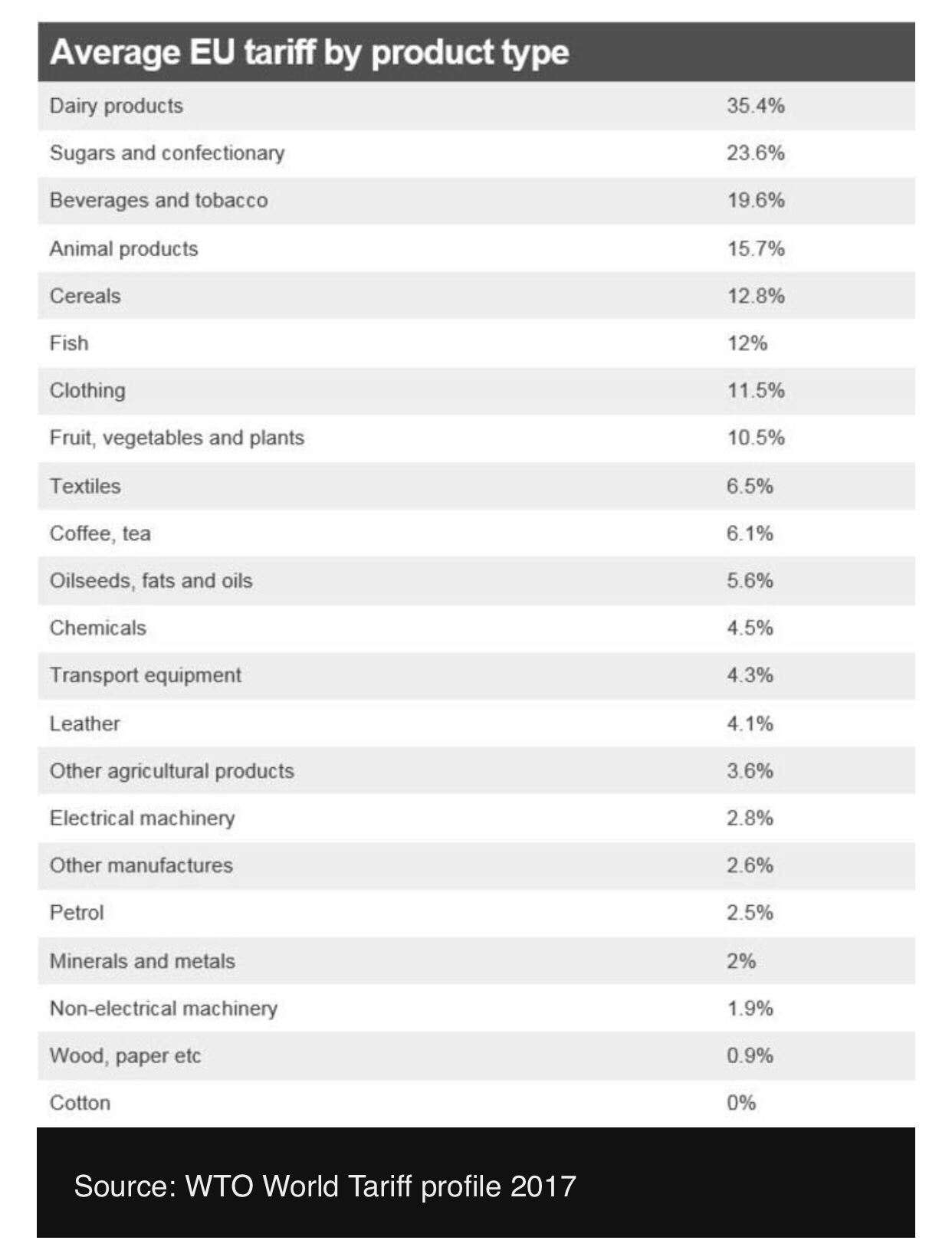

The average EU tariff is pretty low (about 2.6% for non-agricultural products)- but, in some sectors, tariffs can be quite high.

Under WTO rules, cars and car parts, for example, would be taxed at 10% every time they crossed the UK-EU border. And agricultural tariffs are significantly higher, rising to an average of over 35% for dairy products.

After Brexit, the UK could choose to lower tariffs or waive them altogether, in an attempt to stimulate free trade. That could mean some cheaper products coming into the country for consumers but it could also risk driving some UK producers out of business.

It’s important to remember that, under the WTO’s “most favoured nation” rules, the UK couldn’t lower tariffs for the EU, or any specific country, alone. It would have to treat every other WTO member around the world in the same way.

What about other checks and costs?

These are what are known as “non-tariff barriers” and include things such as product standards and safety regulations. Once the UK is no longer part of the EU, there needs to be a system for mutually recognising each other’s standards and regulations. Under a no deal Brexit this may not happen, at least not immediately.

You can argue that it might seem unreasonable if the EU was to go from imposing no checks on UK products at borders the day before Brexit, to insisting on all sorts of checks one day later, even though the UK hadn’t changed any of its rules and regulations.

Doesn’t the UK already trade with many countries on WTO rules?

Yes it does, as part of the EU.

Examples include the United States and China, Brazil and Australia. In fact, it’s any country with which the EU (and therefore the UK) has not signed a free trade agreement. That’s when WTO rules kick in.

But it’s more complicated than that. Those big economies don’t just rely on WTO rules – they also have a series of bilateral agreements with the EU on top of that.

The US, for example, has at leadt twebty agreements with the EU that help regulate specific areas of trade, covering everything from wine and bananas to insurance and energy-efficiency labelling.

In the event of a no deal Brexit, (and an abrupt change in relations), the UK could well have no such deals in place and would be in new territory. Both sides would make efforts to introduce some stopgap measures to keep their economies moving but a last-minute breakdown in negotiations would prove very difficult.

It’s also worth remembering that 44% of all UK exports in 2017 went to the European Union on free trade terms, as part of the single market. That’s down from 55% in 2006 but the EU is still by far the largest UK export market.

“Clearly this is not going to be a situation where all trade stops and there is collapse in terms of the economy as a whole,” said the WTO’s director general, Roberto Azevedo, when he was asked in a BBC interview last year about the potential effect of a hard Brexit on the UK and European economies.

“But it’s not going to be a walk in the park. It’s not like nothing will happen. There will be an impact. The tendency is that prices will go up of course, [because] you have to absorb the cost of that disruption.”

Some people say it won’t be a problem

Yes, some supporters of Brexit argue that no deal is the best way forward, because it would allow the UK to pursue an independent trade policy immediately – to go off and start signing its own trade deals.

That is not the government’s view or the EU’s view, nor is it the view of the vast majority of businesses.

A number of recent articles by supporters of Brexit have made reference to the WTO:s Trade Facilitation Agreement (TFA), which came into force in 2017, arguing that it obliges the EU to treat the UK fairly.

But that doesn’t stand up to scrutiny.

The TFA is aimed primarily at less developed countries and it seeks to encourage transparency and streamline bureaucratic procedures.

It does mean the EU cannot discriminate against the UK but it does not mean the UK can expect to be treated in the same way that it is now.

The UK would be treated like any other third country – and in the absence of any trade agreement, that means tariffs and border checks.

Will the UK have to re-join the WTO after Brexit?

No, it is already a member in its own right.

But it will have to agree a new list of tariff schedules once it is no longer part of the EU.

Like many other parts of the Brexit negotiations, that could be harder than it sounds.

The UK has already submitted documents to the WTO in Geneva, which say that it wants to make a few technical changes to its current commitments as an EU member but otherwise leave them unchanged.

But other countries will want to make sure they are no worse off than they are now after Brexit, while the UK is seeking the same schedules even though after leaving the EU it will represent a much smaller market.

One problem for both the UK and the EU surrounds proposals they have submitted for splitting up their current quotas after Brexit, for the import of sensitive agricultural products such as beef, lamb and sugar from elsewhere in the world. These proposals have already attracted complaints from other countries, including the United States.

And time is running rather short to complete what are always complex negotiations, in which every country will stick up for its own interests.

With a bit of goodwill, the UK hopes it will be able to resolve the debate about WTO schedules. But one of the dangers of a no deal Brexit is that there might not be much goodwill around, especially if it meant that the UK was refusing to pay the more than £39bn it has provisionally agreed it owes the EU as it leaves.

So this is a technical issue, but politics will also play a big role.

Source: Chris Morris, BBC

You must be logged in to post a comment.