3 ways to unleash your creativity

The Formula 1 season will begin later this month, pitting the most talented drivers in the most finely honed machines against one another. James Hewitt has in a WEF article described the essence of creativity using Formula 1 as an example.

The image of a car designer sitting at a computer, working on a complex 3D visualization, is consistent with our perception of a ‘creative person’, but you may not immediately think about the act of driving a Formula 1 car as a creative process.

In fact, drivers are continuously finding inspired ways to take full advantage of every opportunity provided by their car, the conditions and their competitors. The world of Formula 1 represents a fascinating laboratory for exploring human creativity through drivers and their teams.

We can think about human creativity in the context of four components:

[The article writer] was speaking to a colleague recently about the Finnish Formula 1 driver Kimi Räikkönen. We were reflecting on reports of the 2007 World Champion’s exceptional ability to ‘conceptualise three-dimensional space.’ Theoretically, if a driver can simulate a race circuit in their brain in ‘higher-definition’ than another driver, they can imagine more possible scenarios, and take advantage of them.

Kimi has demonstrated a creative approach to his driving from a young age. There is a legendary story from his days racing karts as a youngster. One race weekend in Monaco, Kimi’s kart was knocked over the barrier in a collision. The kart ended up completely off the circuit. The barrier was much too high, and the kart much too heavy, to lift it back over. Undeterred, Kimi continued driving alongside the circuit, on the wrong side of the barrier, until he ran out of road. At this point, Kimi was able to lift the kart onto the track. Kimi jumped back into his kart and worked his way through the pack, eventually finishing third.

Creativity is vital in racing, for teams and for drivers, and it’s becoming increasingly important in the context of knowledge work.

Where the goal of work was once to extract the maximum amount of physical energy from a worker, and transform it into a tangible product, most knowledge work completely disrupts this equation. Knowledge work organisations transform mental energy into ideas and insights – something that will become even more critical as automation replaces many repeatable, process-based tasks.

Last year, the World Economic Forum’ Future of Jobs’ report s identified complex problem solving, critical thinking and creativity as the top three skills required to thrive in the 4th industrial revolution. Both complex problem solving and critical thinking require imagination, innovation and the ability to perceive multiple perspectives. Arguably, this makes creativity the foundation for the ‘podium of future skills’.

Efficient, productivity-orientated tasks are easy to reproduce by another human, or even a machine. Creativity is rare. Creativity is the antidote to the poison of efficiency over effectiveness. It’s the solution to sending endless e-mails and making meaningless presentations, because it allows us to perceive the new opportunities that are unfolding in front of us. While the specific factors that provide the optimal circumstances for creativity are debated, a brute force approach, based on clocking the hours, is not amongst them.

All humans have the capacity to be creative and many of us could unlock more of our creative potential with the right process and conditions. I have heard many people label themselves as “not very creative” but creativity can be expressed in many different ways. For example, creativity may manifest itself as we think of solutions to challenging situations at work, or resolve conflicts, rather than being defined as a tangible creative output.

Previously, it’s been assumed that creativity declines with age. However, in domains that draw on knowledge and expertise, such as writing, philosophy and medicine, research suggests that creative achievement can peak in the early 40s, and declines at a relatively slow rate.

Contrary to popular belief, providing someone with a blank slate does not appear to optimise the creative process. Unbounded choice and opportunity can quickly overwhelm the limited resources of attention, executive function and working memory.

We crave new information and we are rewarded for searching out novelty. In the digital age we have access to a fire hose of content to titillate the reward centres of our brain, but if we don’t have rules and boundaries in place, we can easily become distracted and create little real value.

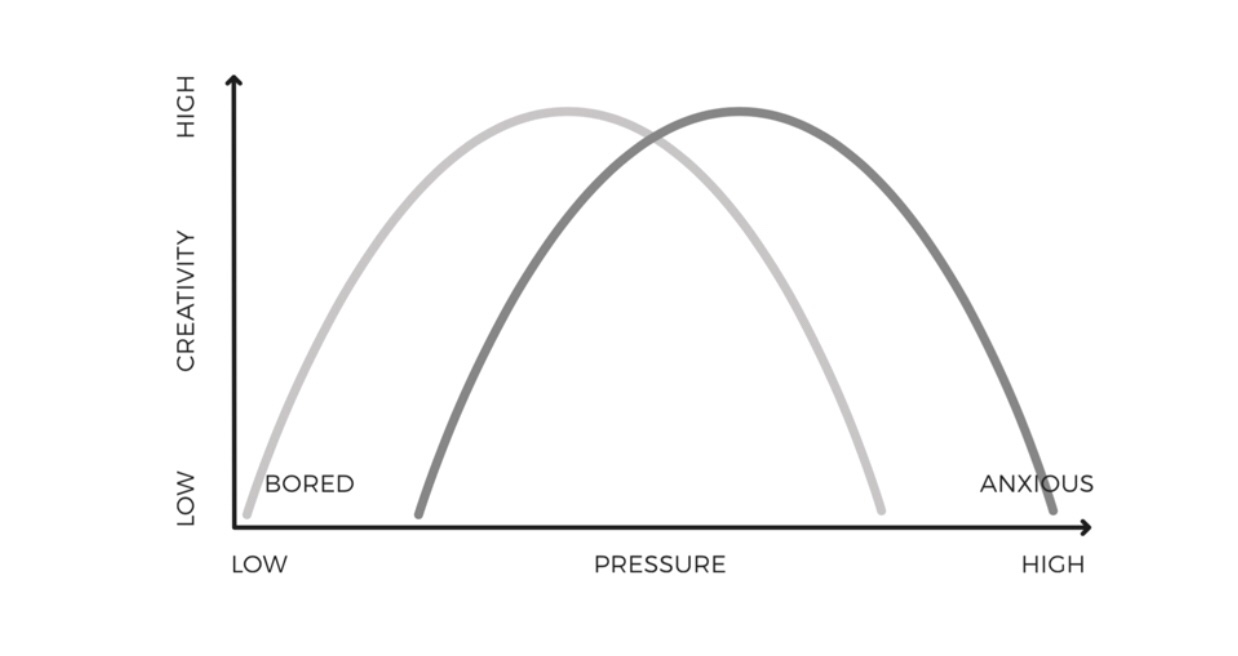

Creativity thrives when there is some pressure and limitation, but not too much. We could plot the creative process as an inverted-U.

Too much time pressure impairs creative cognitive processing, but some pressure can fuel our creativity. Eliminating pressure entirely can suffocate the creative process and create an inhospitable environment for innovation.

Our response to pressure is individual; some people thrive when their backs are against the wall; others prefer a more relaxed approach. For certain individuals, a prize can drive them to produce their most innovative work; others are more motivated by intrinsic rewards. For most of us, it is a combination of the two.

Creativity thrives in three conditions:

1. When we apply and combine old ideas in new ways.

Boundaries force us to look deeper within ourselves, to sift through our experiences for something that could be useful and pool our cognitive resources. Boundaries create the conditions that encourage us to combine what we already know, as well as the new ideas we can come up with.

2. When we feel enough pressure and incentive to encourage flexible thinking.

If we don’t have any pressure or incentive, we can talk forever without actually creating anything. When a clock is ticking, when a reward is waiting and we need to find an answer, our minds are more open to new ways of looking at a problem and we become more cognitively flexible.

3. When we don’t get too comfortable.

When we’ve finally developed an idea that we’re proud of, it’s easy to feel self-satisfied in the afterglow of creative breakthrough. This is one of the greatest risks in the creative process because we can easily become attached to an idea and miss further opportunities for improvement. One way to avoid this state is to regularly move boundaries and change rules (as is the case in Formula 1). This disruption creates a ‘shelf-life’ for your solutions and forces fresh rounds of innovation and creativity.

The development of a Formula 1 car is a good example of what can happen if you provide boundaries and creative conditions for knowledge workers. Team structures combine a breadth and depth of experience that promote the combining of old ideas in new ways. The World Championship competition provides pressure and incentives. Rule changes on an annual basis prevent anyone from becoming too satisfied with their ideas.

A Formula 1 car has thousands of separate elements that must fit together perfectly. A race season could see 30,000 design changes being made to the car, 1,000 per week, as components are tweaked and improved to maximise performance.

The development of a Formula 1 car also illustrates one of the myths of the 10.000 hours rule. Achieving excellence is not the result of countless cycles of mechanical repetition. It works more like a neural network, processes are repeated, but parameters are deliberately adjusted after each cycle of learning, to get closer to the desired result.

Crafting a ‘creative situation’ isn’t just about setting up boundaries for work; it can also involve allocating space for creative reflection. Our brains have a distinct network of interacting brain regions that become active in periods of wakeful rest, such as when we daydream or let our minds wander. This default mode network (DMN) activates whenever we are not involved in a task. Consequently, it’s sometimes described as a ‘task-negative’ state.

Entering ‘default mode’ has strong associations with creative and divergent thinking, comprehension, remembering the past and planning for the future. Some evidence has also observed a positive correlation between creative performance, across all measures of creativity, and the physical volume of the grey matter that makes up the default mode network.

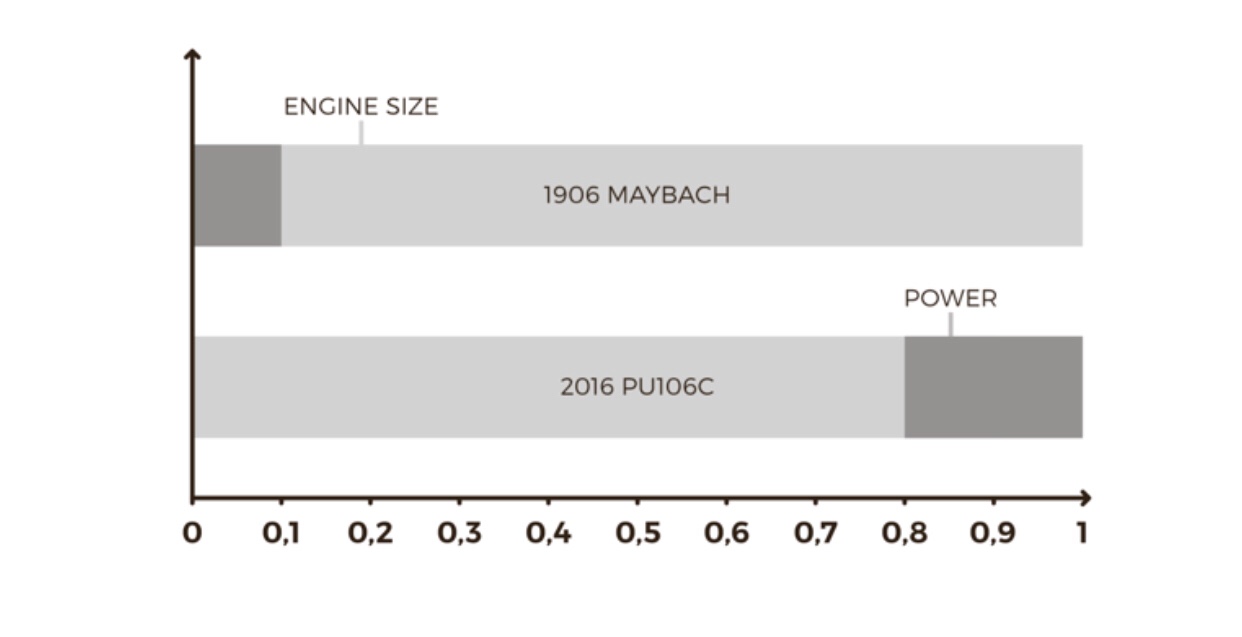

The technical story of Formula 1 describes the importance of quality over quantity and the triumph of creative solutions over brute force. In the 1906 Grand Prix, Mercedes fielded a car with a Maybach designed 11 litre engine. Its beastly engineering produced a mere 78kW of power. 110 years later, Mercedes is still competing and winning Grand Prix. In the 2016 Formula 1 season, Mercedes’ F1 W07 Hybrid cars featured a power unit that produced nearly 10 times the power of the Maybach engine, with 1/7th of the capacity of its ancestor. Brains have replaced brawn with precision, sophistication and consistent creativity.

It is interesting to note that some of the most significant developments in engine design have taken place in the previous four years. Endless cycles of development, testing and refinement, with a hefty dose of ingenuity, mean that today’s Mercedes PU106C power unit delivers at least 47% efficiency, versus 29% in 2013 and around 20% in 1906. These innovations have been instrumentals to the Mercedes’ AMG F1 teams’ three consecutive Constructor’s Championship victories.

There have been greater improvements in the efficiency of internal combustion engines in the last four years than in the last century. When you provide boundaries, resources, and a clear objective, then release people to do their best work, great things are possible.

Three questions to consider

1. Have you considered what level of pressure facilitates your most creative moments?

2. How can you engineer your environment to construct a more hospitable environment for creativity?

3. When did you last enjoy a ‘task-negative’ state and allocate some time for creative reflection?

Source: WEF, James Hewitt

You must be logged in to post a comment.